Introduction

Rolldown is a high-performance JavaScript bundler that Vite plans to integrate as its future default. The bunlding process consists of three major stages: module scanning, symbol linking, and final code generation. I have already written two articles detailing the first two stages, which you can find here:

- How Rolldown Works: Module Loading, Dependency Graphs, and Optimization Explained

- How Rolldown Works: Symbol Linking, CJS/ESM Resolution, and Export Analysis Explained

With those stages complete, we now have a precise "map" of the project — ranging from high-level module graphs to underlying symbol relationships. In this final stage, we leverage this information to generate the actually bundled output. This is the stage that directly impacts your application's loading speend and bundle size.

Code generation strategies

Rolldown utilizes two primary strategies for code generation: Preserve mode and Normal mode. In Preserve mode, the bundler creates separate chunks for every module, maintaining the original module names as filenames. This is a relatively straightforward 1-to-1 mapping often used for library distribution. In contrast, Normal mode is where the core complexity lies; here, Rolldown transforms the module graph into a series of optimized chunks, merged chunks.

This article will focus primarily on the code splitting algorithm that drives this high-performance generation. To wrap up, we will explore the post-processing phase, where Rolldown applies final structural optimizations to the output.

Generate chunks

This section focuses on the core logic of the chunk generation stage. Since the full generation process involves many moving parts — such as handling namespaces, chunk linking, and wrappers — we will narrow our focus to the chunk generation algorithm itself.

The basic structure of this function is straightforward It begins by initializing several key data structures:

let mut chunk_graph = ChunkGraph::new(self.link_output.module_table.modules.len());

// BitSet for each module

let mut index_splitting_info: IndexSplittingInfo = ...;

let mut bits_to_chunk = FxHashMap::with_capacity(self.link_output.entries.len());

let input_base = ArcStr::from(self.get_common_dir_of_all_modules(...));From here, the function branches based on the user's configuration. In preserve mode, the algorithm simply traverses the module table provided by the link_output and creates chunks directly, adding them to the chunk_graph. This mode is always used by library authors who want to keep their files seperate instead of merging them — for several specific, high-value reasons.

-

Better tree-shaking. Allows the user is able to import only the necessary parts of a library, ensuring they don't ship "dead code" to their users.

-

Deep imports. It lets users import specific parts directly (e.g.,

import Button from 'ui/Button') because the file strucutre remains the same as your source code. -

Easier debugging. The output folder look exactly like your source folder, making it much easier to read and troubleshoot errors in the browser.

-

Atomic updates. If you change one file, ony that specific file changes. This is better for caching and environments that load modules on demand.

However, for normal mode, Rolldown adopts a more sophisticated approach to transform the module graph into an optimized set of bundles.

Normal bundling mode

This is the standard mode for most JavaScript projects, where Rolldown transforms the module graph into a series of optimized chunks. The process begins by identifying entry points based on the user's configuration, then traversing the graph to find every reachable module. To balance control and performance, Rolldown first executes manual splitting, carving out high-priority modules based on user-defined rules. Once these specific requirements are met, the remaining "unclaimed" modules are processed via an automatic splitting algorithm. Finally, the process concludes with a structural optimization phase, where Rolldown cleans up the result by merging duplicated modules and removing redundant facade chunks to ensure final output is as lean as possible.

Entry point creation

Since module traversal begins at the entry points, initializing them is the first critical step of the process. In the context of bundling, an entry point is essentially a specialized module that serves as a root for the dependency graph. During this phase, Rolldown iterates through the entry_points defined in the link output and initializes a corresponding chunk for each one.

The most vital piece of metadata for these entry chunks is the bits field. While we will explore the algorithm in detail later, bits is essential a wrapped data structure that functions like a bitmask. The total length of this bitset corresponds to the number of entry points in the project, which each entry being assigned a unique bit position.

The same logic is extended to every normal module in the graph. By using bit positions to record which entires can reach a specific module, Rolldown creates a "reachability fingerprint". This fingerprint is the foundation of the code splitting algorithm, as it allows the bundler to determine exactly which modules are shared between entires and which remain private.

Split chunks

The split_chunks function is the engine that transforms a raw module dependency graph into an efficient chunk allocation strategy. Its primary goal is to balance automated efficiency with explicit user control, ensuring that the final bundle structure aligns with both performance best practices and specific project reuqirements.

The process begins with entry analysis, where the determine_reachable_modules_for_entry function performs a Breadth-First Search (BFS) across the module graph. Starting from each entry point, the algorithm visits every reachable module and assigns the corresponding entry_index to the module's bitset. This creates the "fingerprint" mentioned earlier, allowing Rolldown to identify exactly which entires depend on which modules.

Once reachability is established, Rolldown moves into manual splitting. Because developers often possess business logic context that an algorithm cannot infer, user-defined groups — configured via regex patterns or custom functions — are processed first. By carving out these high-priority modules into specific chunks before the automated logic takes over, Rolldown ensures that user intent always takes precedence.

Following the manual phase, the remaining modules undergo automatic allocation. Here, modules are grouped based on their bitset patterns to ensure that the resulting chunks are neither too large for efficient loading nor too small for optimal HTTP performance. Finally, the function performs a cleanup pass to merge and optimize the resulting chunks, resolving any structural redundancies.

Ultimately, this multi-phased approach treats the user's configuration as the primary blueprint, leaving the algorithm to solve the remaining "puzzle" of shared dependencies.

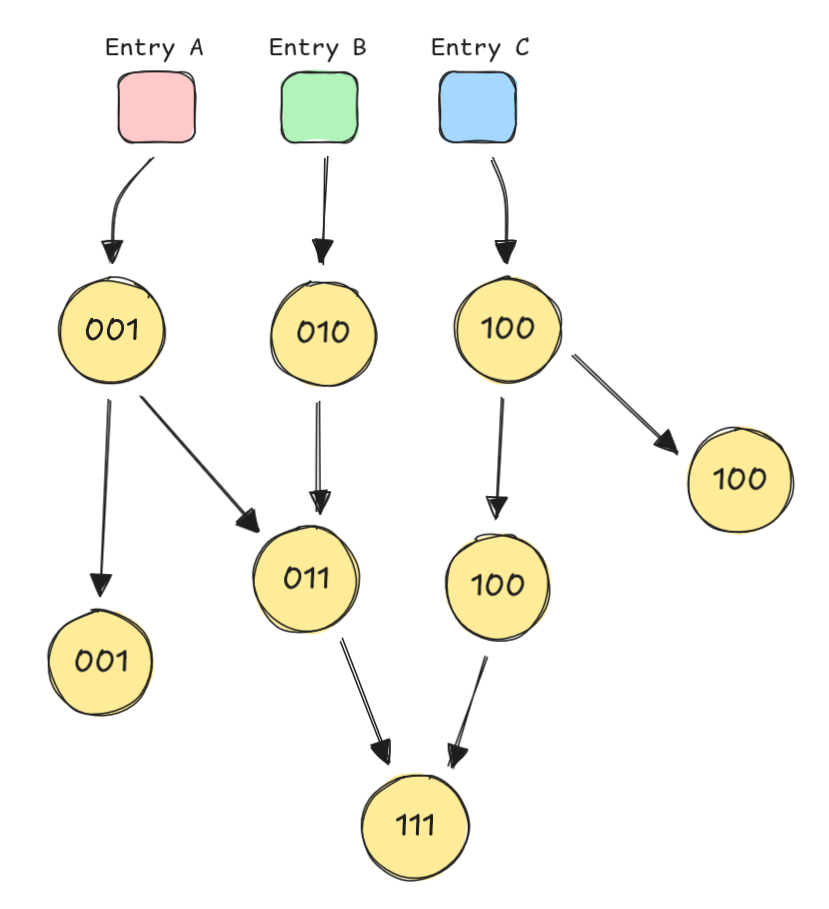

Phase 1: Defining Reachability (The BitSet Fingerprint)

The first step of the code-splitting algorithm is to analyze reachability: determining which modules can be accessed from which entry points. In Rolldown, an entry is a root module — of which there are three different kinds📝 — that serves as a starting point for a chunk. By tracing the graph from these entries, Rolldown marks every reachable module to ensure that topological relationships remain intact after code splitting. This is critical because, in the final bundle, each chunk is a separate file loaded asynchronously by the browser; if reachability is broken, the application will fail to resolve its dependencies at runtime.

To map this out, Rolldown utilizes a classic breadth-first search (BFS) on the module graph. Starting from the entry points, the algorithm traverses all included modules, updating their "reachability data" as it goes. This data is stored in an array of SplittingInfo structures, indexed by the module's unique ID:

// Type definition for SplittingInfo

pub struct SplittingInfo {

pub bits: BitSet,

pub share_count: u32,

}

// Updating info during traversal

index_splitting_info[module_idx].bits.set_bit(entry_index);

index_splitting_info[module_idx].share_count += 1;The core of this structure is the bits field — a bitmask where the length corresponds to the total number of entry points. Each entry point is assigned a specific bit position. For instance, in a project with three entries, the mapping might look like this:

| Entry | Bit |

|---|---|

| Entry A | 0 |

| Entry B | 1 |

| Entry C | 2 |

The algorithm would be as follows:

If a module is reachable from Entry A, the 0th bit is set to 1. If it is also reachable from Entry C the 2nd bit is also set, resulting in a binary representation like 101. This "fingerprint" becomes the definitive signature for the module, later determining exactly which chunk it belongs to or whether it needs to be moved into a shared chunk.

Phase 2: User-Driven Partitioning (Manual Splitting)

Once reachability is defined, Rolldown begins the first round of code splitting. This phase is driven by manual splitting rules — specifically match groups📝 — which allow users to explicitly define how certain modules should be bundled. Because these rules represent direct developer intent, they take priority over the automatic algorithm and are processed first.

The engine behind this phase relies on two primary data structures: a map to link group names to indices, and a vector to store the actual group data.

// Maps user-defined group names to their internal index

let mut name_to_module_groups: FxHashMap<(usize, ArcStr), ModuleGroupIdx>

// Stores the actuall module group data

let mut index_module_groups: IndexVec<ModuleGroupIdx, ModuleGroup>

You can think of a ModuleGroup as a bucket. It doesn't just hold a name and a set of modules; it also tracks priority and total size to inform later splitting decisions.

struct ModuleGroup {

name: ArcStr,

match_group_index: usize,

// Modules belonging to this group

modules: FxHashSet<ModuleIdx>,

priority: u32,

sizes: f64,

}

The assignment process

Rolldown iterates through every module and tests it against the user's match group configurations. If a module matches a rule and satisfies the defined constraints — such as allow_min_module_size or allow_min_share_count — it is assigned to a corresponding group. Crucially, this isn't just a surface-level match; Rolldown uses add_module_and_dependencies_to_group_recursively to ensure that a module's entire dependency tree is pulled into the group, preserving the integrity of the manual chunk.

After assignment, the groups are stored by priority. If priorities are equal, the algorithm falls back to the original index and then dictionary order to maintain a stable, predictable sorting result. The final list is then reversed, preparing it for the "greedy" splitting logic.

Refining the groups

Even though a user defines a group, the resulting "bucket" might be too large or too small for optimal performance. Rolldown performs a "greedy" refinement process to ensure each group stays within a reasonable size range. This is handled through a sequence of logic steps rather than a simple cut.

First, modules within a group are pre-sorted by size and execution order. By placing smaller modules at the begining of the vector, Rolldown can more easily carve out segments that meet the minimum size requirements without being blocked by a single massive module.

The algorithm then attempts to split the group greedily. It scans from both ends to find two segments that each exceed the allow_min_size. The left segment becomes a potential new chunk, while the right segment serves as a validation check. If these segments overlap, the group is kept whole to prevent the creation of tiny, inefficient files that would degrade browser loading performance.

If a split is valid, Rolldown expands the left segment as much as possible — adding modules until it hits the allow_max_size limit. This minimizes the total number of chunks, which is generally better for HTTP/2 multiplexing. Any remaining parts of the group are pushed back onto a stack to be re-evaluated and potentially split again in the next iteration. Once a chunk is successfully finalized, its modules are removed from all other groups to prevent duplication.

Phase 3: Automated Allocation (The Core Loop)

After manual assignment handles high-priority modules, Rolldown executes the automatic allocation for the remaining codebase. This algorithm assigns modules to chunks based on their bits (reachability fingerprints) and intelligently creates shared chunks for modules belonging to multiple entires.

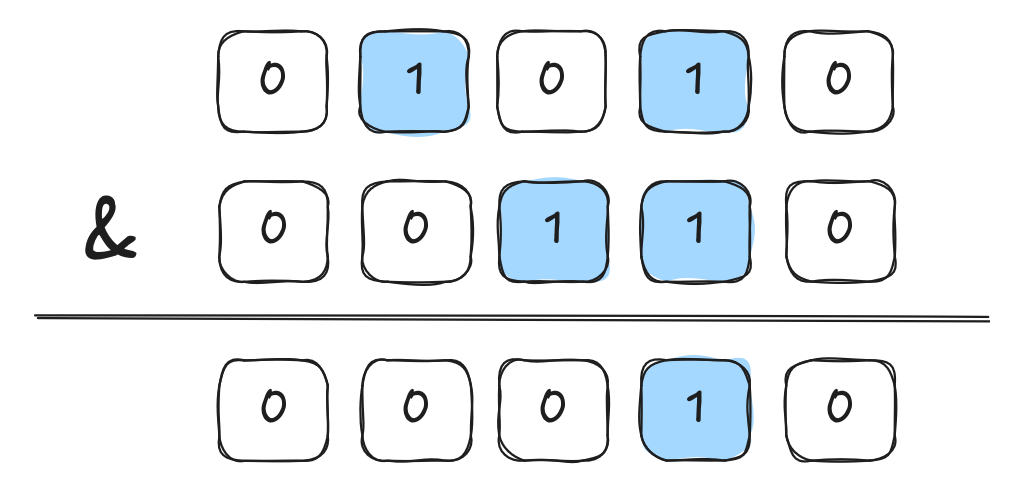

A bitwise "warm up"

To understand the beauty of this algorithm, let's look at a seemingly unrelated challenge: the Find the Prefix Common Array LeetCode problem.

The problem asks us to compare two permutations, and , and find how many common elements they share at each index . While a hash map would work, bit manipulation is far more elegant and efficient. By representing the presence of a number as a bit in a bitmask (e.g., the number 3 sets the 3rd bit), we can compare two sets using a simple bitwise AND () operation.

The number of set bit (bit_count) in the result tells us exactly how many elements the two arrays share. This operation is lightning-fast because it leverages hardware-level instructions.

def findThePrefixCommonArray(self, A: List[int], B: List[int]) -> List[int]:

a, b = 0, 0

ans = []

for x, y in zip(A, B):

a |= 1 << x

b |= 1 << y

ans.append((a & b).bit_count())

return ansApplying the logic to Rolldown

What does this have to do with bundling? In Phase 1, we asigned each entry point a unique bit position. Just as the bitmask in the LeetCode problem represents a set of number, the bit field in Rolldown represents the set of entires that can reach a specific module.

This means the bits value acts as a unique key for a module's reachability. If two modules have the exact same bits value, they belong to the exact same set of entires and should, therefore, live in the same chunk.

let bits = &index_splitting_info[normal_module.idx].bits;

if let Some(chunk_id) = bits_to_chunk.get(bits).copied() {

// Add module to chunk

}

// ...

Pretty straight forward, right? This logic allows Rolldown to group modules into shared chunks automatically. However, the production implementation handles several specialized cases to ensure the best performance.

-

Case A (the common case): If the bitset matches an existing chunk, the module is added there.

-

Case B (facade prevention): For user-defined entries, Rolldown tries to keep modules within the original entry chunk even if they are technically shared. This prevents the creation of facade entries📝 — tiny files that do nothing but re-export code from a shared chunk. Minimizing these facades reduces the total number of HTTP requests, which is vital for initial load performance.

-

Case C (pending optimization): Certain modules are marked as "pending". These are held back for a smarter merging phase later, as they require more context about the overall bundle structure to be placed optimally.

-

Case D (the default): If the bitset is entirely new, Rolldown creates a new common chunk and records the mapping so future modules with the same bits can join it.

Phase 4: Structural Optimization (Merging & Facades)

Because these optimization algorithms involve complex edge cases that could fill an entire article on their own, we will focus on a high-level conceptual understanding of how they refine the bundle.

The first optimization involves merging common modules into existing chunks. Rather than reflexively creating a new shared chunk for every shared dependency, the optimizer scans through the "pending" common modules and attempts to "tuck" them into an existing entry chunk. This is only done if the move is deemed "safe". In this context, safety means the merger must not violate dependency ordering, cross asynchronous boundaries, break dynamic import logic, or later the expected API shape of the chunk. By consolidating these modules, Rolldown reduces the total "chunk count", which minimizes the overhead of managing multiple files in the browser.

The second optimization is handled by the optimize_facade_dynamic_entry_chunks function. During the earlier splitting phases, some entry chunks may become "empty" because all their internal modules were moved into shared chunks. This leaves behind a "facade" — a file that contains no logic of its own and only exists to point elsewhere. This optimization identifies these redundant files, removes them, and patch the symbol references and runtime logic so the application behaves as if the facade still existed. This is a crucial step for maintaining a clean output, especially in large-scale projects with complex dynamic imports.

Post processing phase

The final stage of the pipeline involves a series of refinements to ensure the generated chunks are clean, logically ordered, and optimized for performance. This phase primarily focuses on merging external namespaces, sorting modules and chunks, and streamlining entry-level external modules.

Merge external import namespaces at chunk level

During the link stage, Rolldown collects external namespace✨ import symbols and groups them by their respective external modules. You can read my previous article if you're interested. Once the chunks are finalized, we can begin merging and linking these symbols at the chunk level.

The process is highly efficient. Rolldown first re-groups these symbols according to the chunks they belong to. In a typical project, multiple modules might import the same external namespace (like React); if these modules end up in the same chunk, there is no need to keep redundant references. After confirming that the modules are actually included in the final bundle and sorting them by execution order, Rolldown links all identical namespace symbols in a single chunk to the first used instance.

Before Merging:

// Module A (in Chunk 1)

import * as React_1 from 'react';

// Module B (in Chunk 1)

import * as React_2 from 'react';After Merging:

// Rolldown keeps only one namespace reference

import * as React_Namespace from 'react';

// All code that originally used React_1 or React_2

// is rewritten to use React_Namespace

console.log(React_Namespace.useState);Sort, find entry-level external modules

Consistency is key to a stable build process. To achieve this, all modules within every chunk are sorted by execution order. The chunks themselves are then sorted according to their type: entry chunks take priority, followed by static chunks, and finally dynamic chunks. This ensures a stable, predictable order across different entry points.

A final, elegant optimization occurs with entry-level external modules. These are external modules reachable from an entry point through an unbroken chain of export * statements.

Example scenario:

// entry.js

export * from './a.js'

// a.js

export * from 'external'Normally, Rolldown would need to generate complex interoperability code (using the __reExport runtime helper) to bridge these files. However, if the chain remains unbroken, the function detects this "entry-level" status and outputs a simple, clean import:

import * from 'external';However, there is a vital exception to this rule: if the code explicitly references the namespace object itself — rather than simply passing through the exports — Rolldown must bypass this optimization. This ensures that the namespace object remains fully populated and spec-compliant, preventing any missng symbols that might occur with a direct re-export.

Summary

The journey from a raw module graph to a production-ready bundle is a balancing act between developer intent and algorithmic efficiency. By leveraging a BitSet-based reachability fingerprint, Rolldown transforms complex dependency relationships into a high-performance bitmask, allowing it to identify shared modules with hardware-level speed.

The real beauty of this final stage is how it balances developer intent with algorithm muscle. You get the control of manual splitting when you need it, but the "smart" defaults handle the headache of facade chunks and namespace merging behind the scenes. Whether you're shipping a library or a massive web app, the goal remains the same: less bloat, faster loads, and a cleaner output.

This concludes our deep dive into the Rolldown pipeline. From scanning and linking to this final generation stage, the focus remains clear: bringing the performance of Rust to the flexibility of the JavaScript ecosystem, one bit at a time.

But don't think we've reached the finish line just yet! 😉 This is only the beginning of our journey through the Rolldown codebase. There are still plenty of fascinating corners to explore. I’ll be back with more articles soon to break down these "hidden gems" and share more my understanding of what makes this bundler tick. Stay tuned!